Project structure and source code

The source

code for the project is hosted in ‘powershell.sample-module’

GitHub repository. The repository contains both the code for the sample

PowerShell module and the configuration for its build process. I put all the

module sources into ‘SampleModule’

folder and keep everything else in the project root. This structure makes the

sample more reusable so that you can fork or clone the repository to your local

machine and make it fully workable with a minimum of tweaks.

If you check

the module definition in ‘SampleModule.psm1’

file, you might find it somewhat minimalistic. Basically, it doesn’t contain

any functions and serves as a load script for individual function definitions

located in the ‘Public’ and ‘Private’ subfolder. People who already familiar

with PowerShell module development might immediately recognize a definitive

pattern when a module has some public functions to be exported and, optionally,

some internal helper functions invoked from the public ones and not accessible

to a third party. This pattern encourages you to define each function in a

separate file and maintain a clean and intuitive codebase.

For the sake

of simplicity, the module contains only one public function, which generates a

range of GUIDs based on the input parameter. It has no fancy logic, just a

function definition according to general PowerShell guidelines.

Pester

tests

All project

tests are implemented with the Pester test

framework. What I like the most about Pester is that you write your test cases

in the same PowerShell language, and, as a result, you can use the same

scripting logic to make your tests dynamic. For example, ‘SampleModule.Tests.ps1’

file contains some project-level tests that will be executed against the module

definitions and all existing and future function definitions.

As functions

generally implement different logic, these top-level tests for functions ensure

only common code style and comment-based help quality. Individual function

logic is tested with separate ‘functional’ test cases, which are defined in

separate ‘*.Tests.ps1’ files.

If you look

at test files from the project structure point of view, you can notice that I

prefer to keep the test files alongside the source code they test. In that

case, it is visually easier to check whether you have defined test cases for

the specific part of your project.

Apart from

that, I defined a separate set of project-level tests in ‘SampleModule.PSSATests.ps1’

file. This test file serves as a wrapper for PSScriptAnalyzer, which checks the

PowerShell code for coding standards. In my example, I just perform static code

analysis with the default rules, but you can define your custom rules to ensure

specific code standards for all your project code.

Build

script and dependencies

Now, when we

have looked into the source code and the tests, it’s time to talk about how we

are going to build our sample module. As I mentioned in my previous

post, there is no need to reinvent the wheel and create your custom build

tool. In my example, build automation is implemented with InvokeBuild,

and all the build tasks are defined in a single ‘SampleModule.build.ps1’

file. This build script is well-commented, so I encourage you to go and look

into its source code. Also, don’t forget to check InvokeBuild

wiki for better understanding the features and specifics of the build

framework itself.

If you just

want to test out the build script on your local machine, install the InvokeBuild

module, and type ‘Invoke-Build ?’ in a PowerShell session in the root

project folder. For example, if you type only ‘Invoke-Build’ without any

options, the default task will be executed, and a build will be produced in the

‘build’ folder.

That’s it.

There is no need to manually download or install any other modules, packages or

software, as all build dependencies will be handled by PSDepend (look

for ‘Enter-Build’ script block in the build script). The build dependencies

itself are specified in ‘SampleModule.depend.psd1’,

which is just a simple PowerShell data file. PSDepend will go through the list

of required modules in that file, downloads and installs them in your build

environment.

Azure

DevOps pipeline

If you

managed to get to this part, now you should have managed to build your project

locally. “What about the CI/CD pipeline?” you might ask. Let’s put computers to

work instead of us.

In my

example, I used Azure

Pipelines to perform all the tasks required to test, build and publish

the module.

If you check

the pipeline configuration in ‘azure-pipelines.yml’

file, you might see that continuous integration is pretty straightforward. The

pipeline steps just invoke specific tasks, which are already defined in the

build script. This allows you to keep build and pipeline logic separate from

each other and easier to maintain.

As

PowerShell script modules don’t require compilation into binary format, for the

sake of pipeline run time, I perform all tests and code quality checks first

and then assemble the module package itself. If the project doesn’t pass the

tests, there is no need to waste time producing a build. Basically, the test

stage contains all the quality build gates: no failing tests, no

PSScriptAnalyzer rule violations, acceptable code coverage level. All test

results are published as artifacts and can be evaluated on the build results

page.

Also, the

build and publish stages are configured to produce ‘official’ builds only from

the master branch.

The pipeline

references a few pipeline variables that are project-specific:

- module.Name – the name of your

custom module;

- module.FeedName – the name of

you PowerShell repository feed to publish your module;

- module.SourceLocation – the

repository feed URL.

The last two

are required to automatically version and publish the module in the Azure

Artifacts feed.

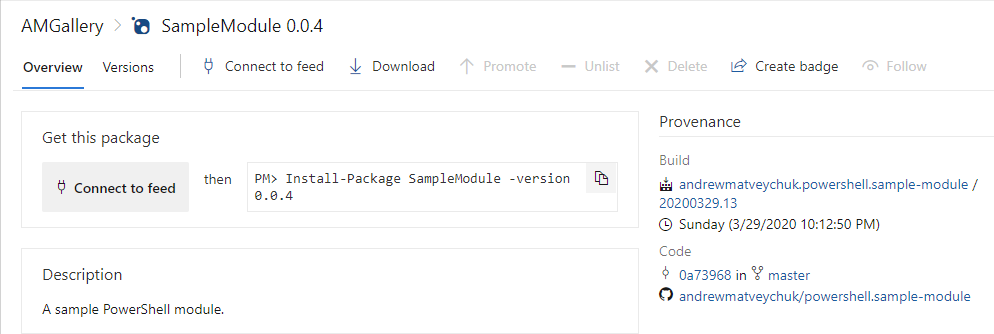

Azure

Artifacts as PowerShell repository

As

PowerShell modules were intended to be reusable tools, it’s a good idea to have

them hosted in a PowerShell repository for consumption by other people and

processes. With Azure DevOps, you can use Azure Artifacts to host both public and private PowerShell

repositories for your modules.

PowerShell

repositories mostly based on regular NuGet feeds, and module packages in them

are basically NuGet packages. To pack my sample module into a NuGet package, I

defined its specification in ‘SampleModule.nuspec’

file.

In my

example, when creating a release build, the build script will query the target

feed for an existing module package and version the current build based on the

current published module version. The build will be published as a pipeline

artifact and, at the publish stage, will be pushed to the target Artifacts

feed.

No comments:

Post a Comment